The prospect of A.I. and the many fortunes it will bring humanity, is seemingly driven by the unshakeable faith that is deeply rooted far beyond it is Silicon Valley headquarters. Harmony and prosperity is believed to relinquish our burdens of daily routines. The possibility of choices cause distress in the terms of this techno-cult. Freedom is to be dispelled as it only limits your purposes. What good could we do, if we were not strained by those troublesome nuisances (What shall I buy? What shall I do? What shall I believe?) Think of all the time we could spend on projects, dreams or just ourselves, if someone – or rather something – would take care of this.

The reasonable anxiety toward the idea that machines will eventually taking over humanity goes back to early industrialisation, when Julien Offray de La Mettrie imagined a transformation from human to a machine in L´homme maschine (1748), one solely driven by pleasure and lack of pleasure, like and dislike. When smartphone owners consult their devices about 150 times a day (as according to a recent study) hoping for short moments of relief and distraction, La Mettrie’s visions have a strange truth to them. Likes do function as rewards. However, what we consume from these devices is meaningless in he end, attention is what matters. The more time we spend, the more valuable one becomes as every bit of information about us is absorbed.

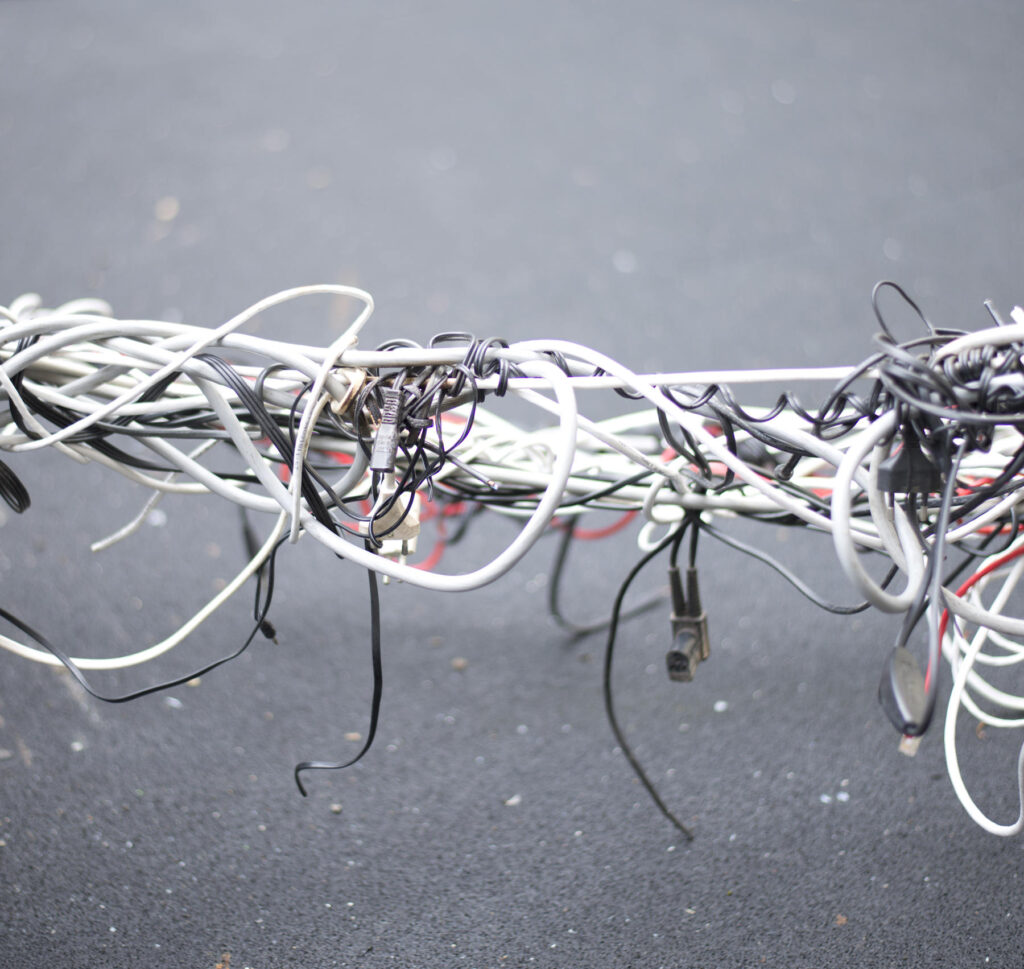

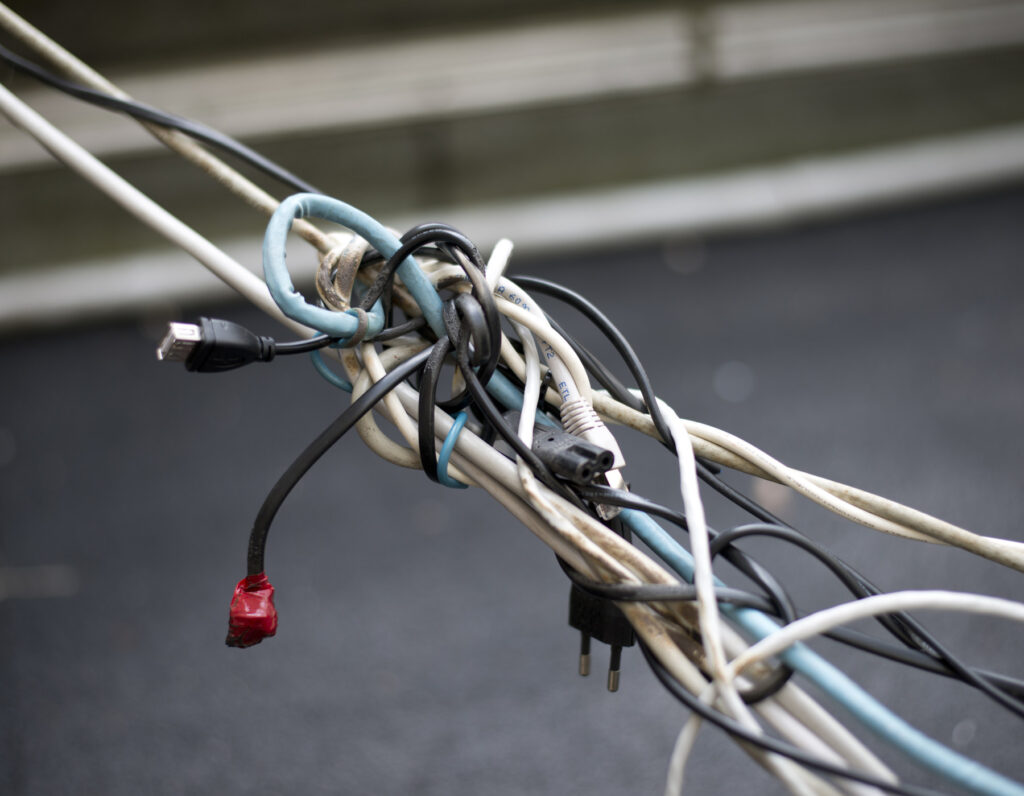

Joachim Coucke works with installation and sculptures that investigate our broken relationship between the physical and digital realm. Developing a body of works that envision a rather uneasy future, Coucke is raising attention to the aspect of ethical and moral debates that arise from current technofied euphemisms. By using an ever lasting supply of outdated computer hardware, his works unveil an anachronistic bizarreness which is usually unregarded in our not yet fully digitalised and immaterial civilisation. All that is fluid and ethereal, allowing information to flow, has indeed a physical equivalent. When an algorithmised life tries more and more to detach sensation from ones body, these accumulations of technological waste, seem unreal, but indeed are and ever growing.

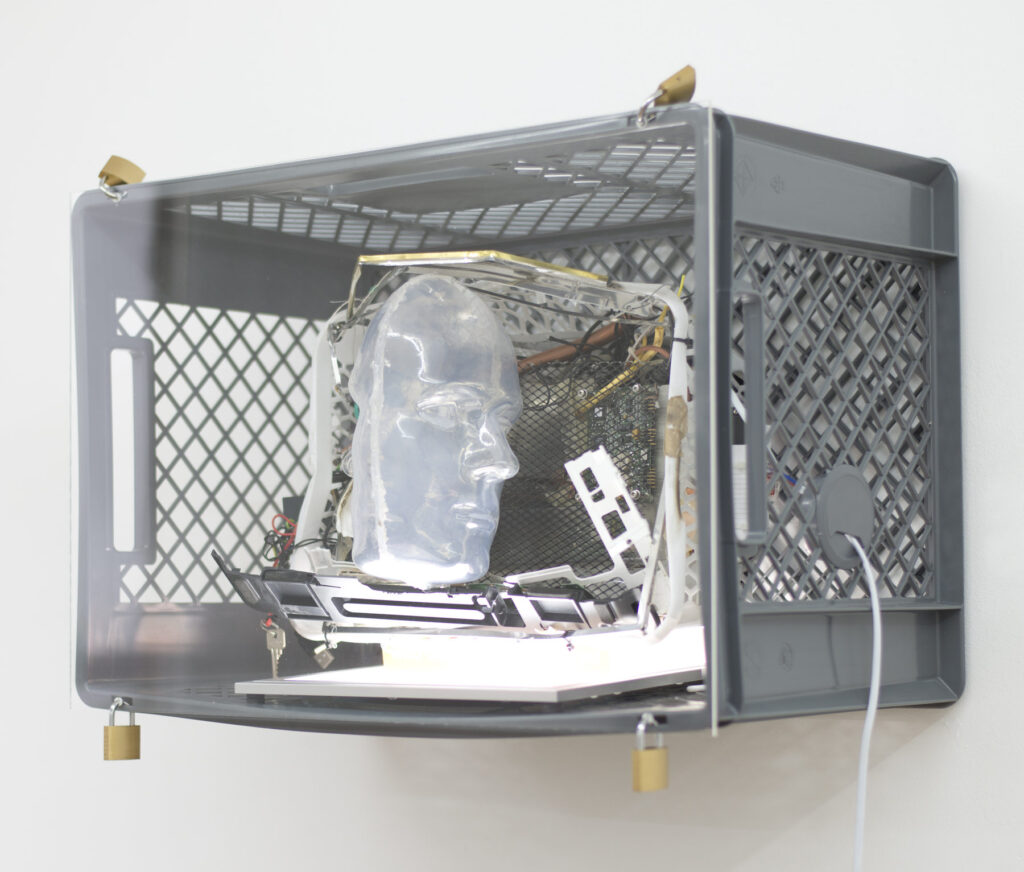

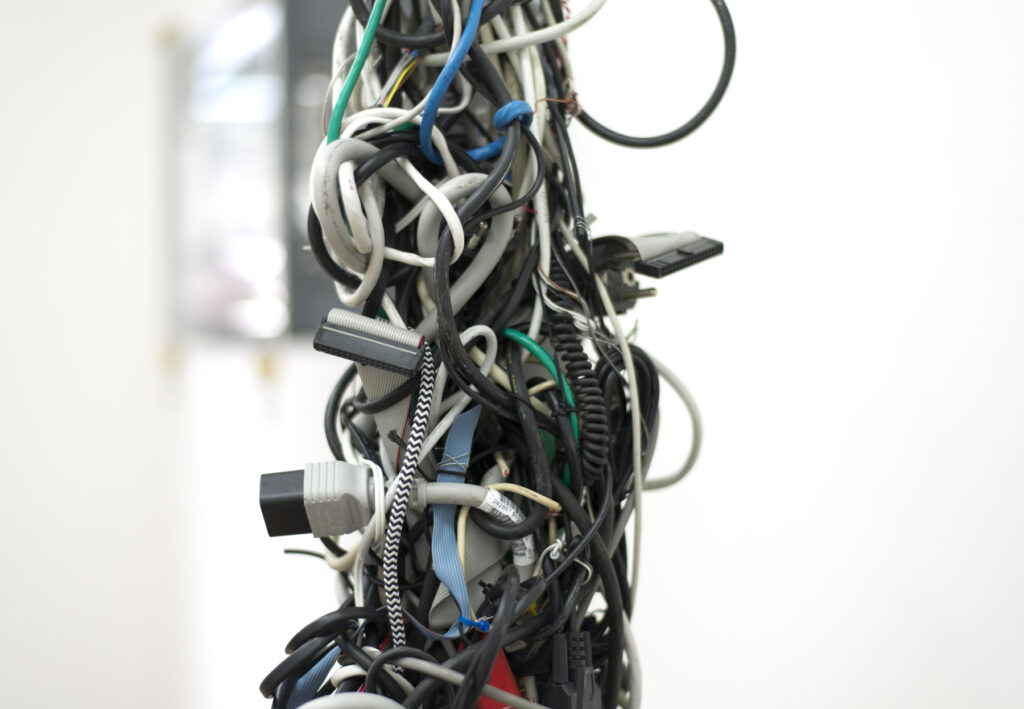

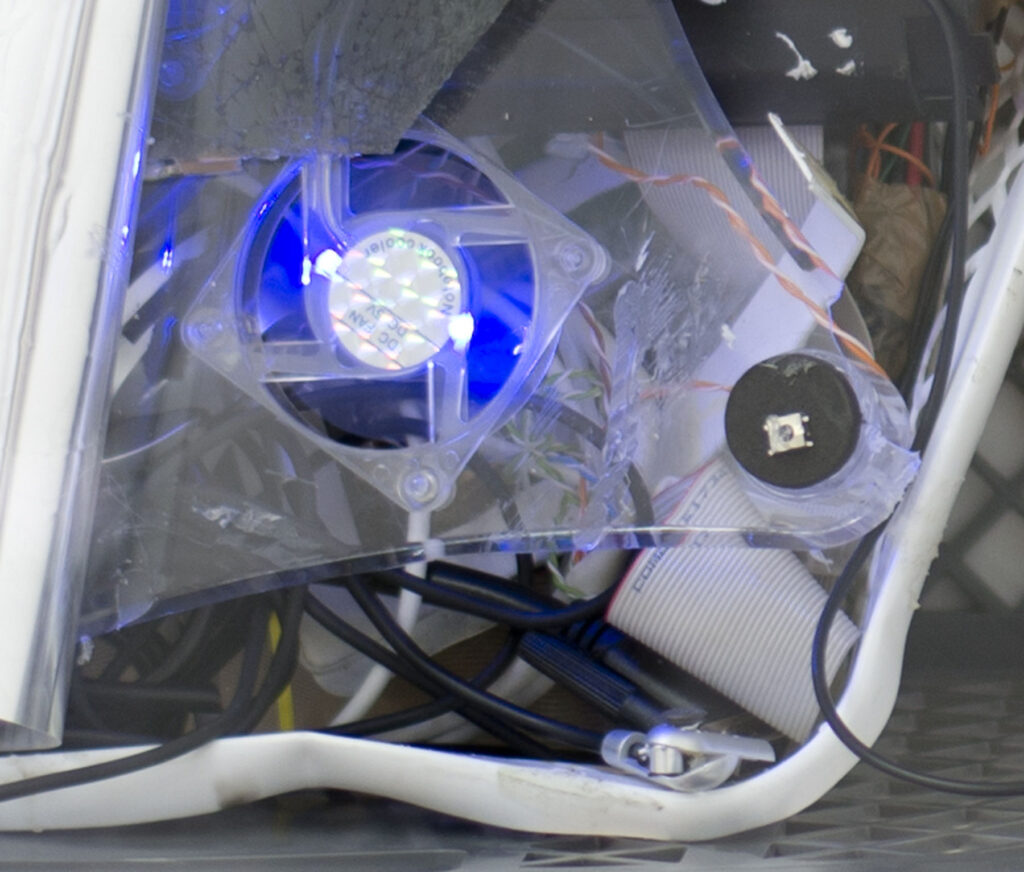

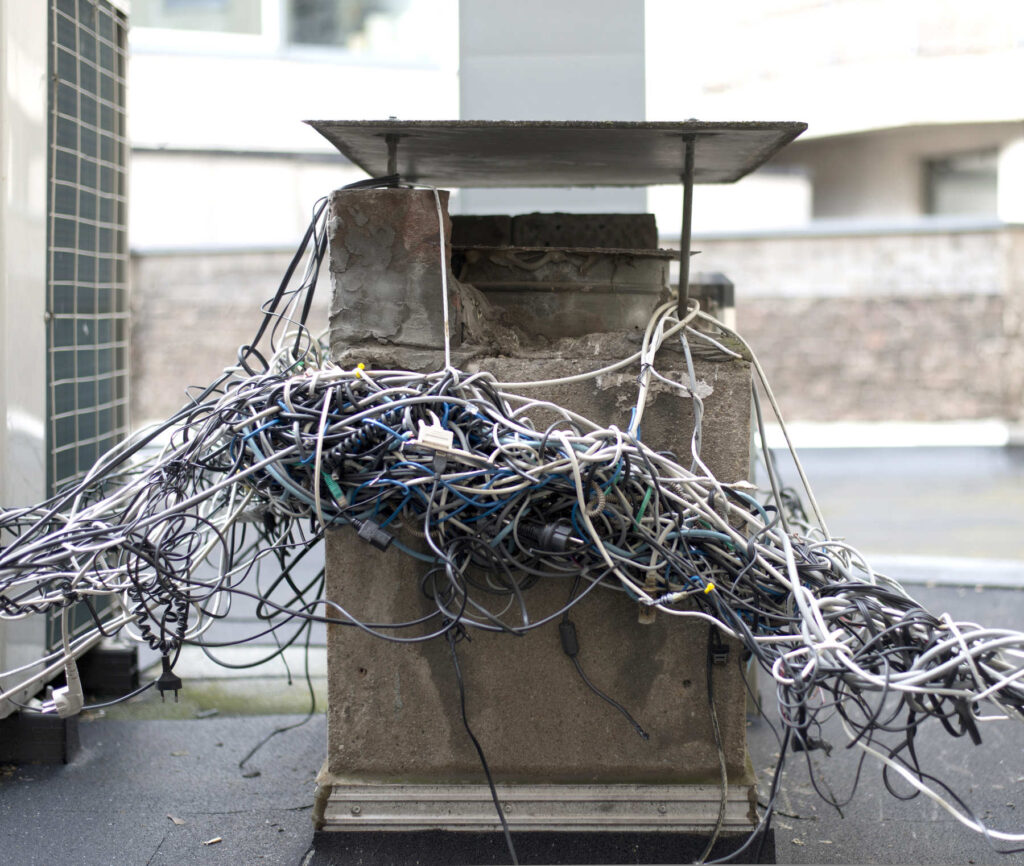

As such, human-sized sculptures made out of networks, USB and power supply cables are hanging from the ceiling – like ripe fruits from a tree, while another of these cable sculpture is lurking on the rooftop of MÉLANGE. They speak of entanglement and being lulled ̶ quite the opposite of liberation. Along these sculptures, plastic boxes containing technological still-lifes are on display, made of broken computer screens, but also more recent components. Instead of skulls, translucent plastic masks are used. As glass separates the viewer from the content, they allude to the idea of showcases but even more of shrines both of which seek to attract someones praise, and therefore their time. Praying for ones fortunes, one should be cautious about his or her wishes, as the machine’s will is programmed to be efficient, in every possible way.

Heidegger was concerned with technology being meant to produce a reservoir of time, with the goal immunising man against change. All of that collected data is saved to remember, to have everything at one’s disposal at any given time. Technology therefor, as stated by him, is used to liberate man from his physique, fate and accident. But when one’s life becomes quantified by the meaning of being literally calculable, one should be aware of what is to come.

JOACHIM COUCKE, born in 1983 in Kortrijk, is an Artist and Curator (Co-Founder of DASH), living in Waregem, Belgium. He graduated HISK Laureate in Gent 2012. His work has been included in several solo and group shows at Yoko Uhoda Gallery (2016, Liege), Johannes Vogt Gallery (2015, New York), CCA Ujazdowski Castle (2014, Warsaw) and many others.