Here is fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop

– Billie Holiday, Strange Fruits 1939

Culture often manifests itself through strong images; images that attract and batter us. Billie Holiday’s song “Strange Fruits” as sad and beautiful as it is, illustrates the hanging of people from a tree, their corpses slowly withering away. A dark foreboding evokes unrest. The tree, a symbol of growth and life, transforms into death. This metamorphosis of the tree, its passive way of participating in violence, is inherent in its strong rooted nature. As it stands tall – growing, dying, ever changing – it offers humans a choice to use it. Becoming an instrument of life, torture or death. An agent of internalized violence; in monoteistic religions we can find it in the garden of Eden, a walled and protected paradise, but yet a predator (snake) found its way into this realm. These walls seemingly keep threats out, protect the integrity of the garden, without realizing that those malicious thoughts might already be inside. Here the tree becomes the stage for betrayal. Our ancestors dwelled in trees, worshiped them and snakes can climb them.

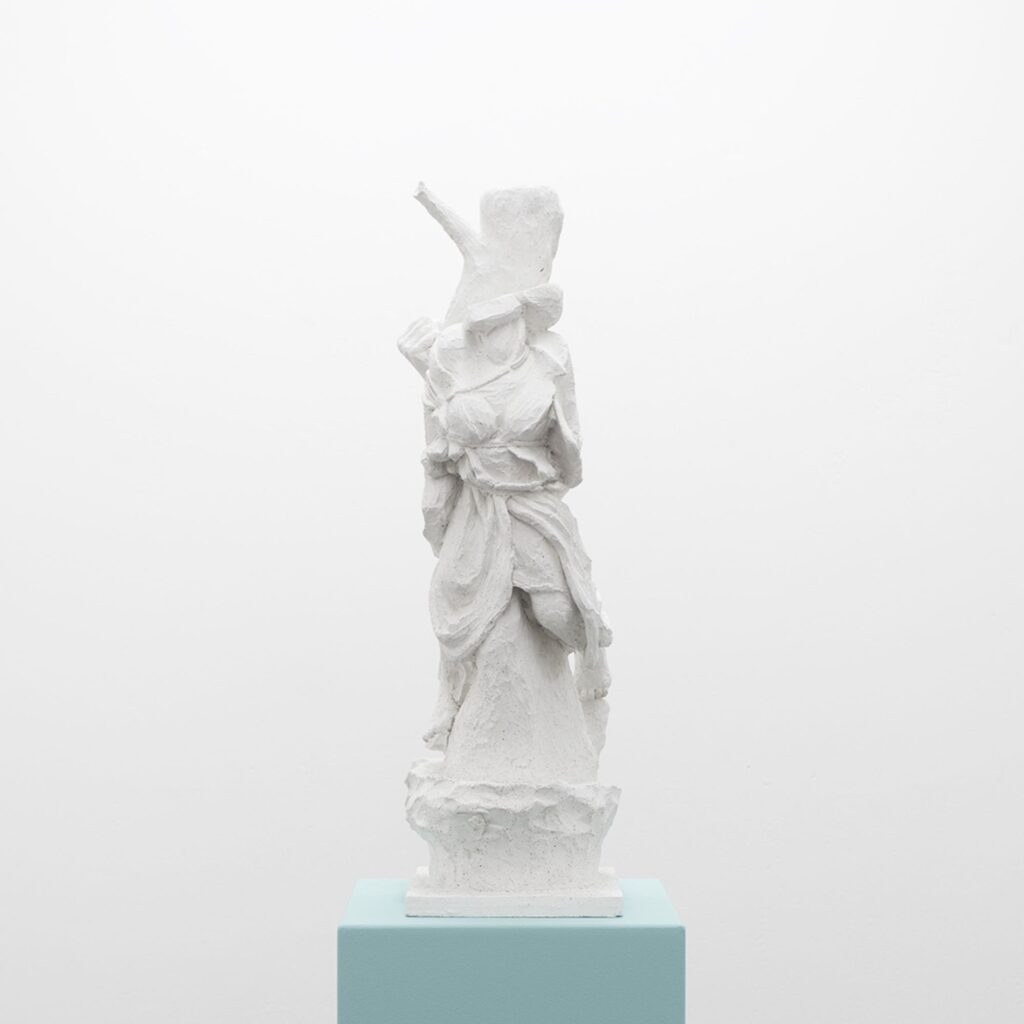

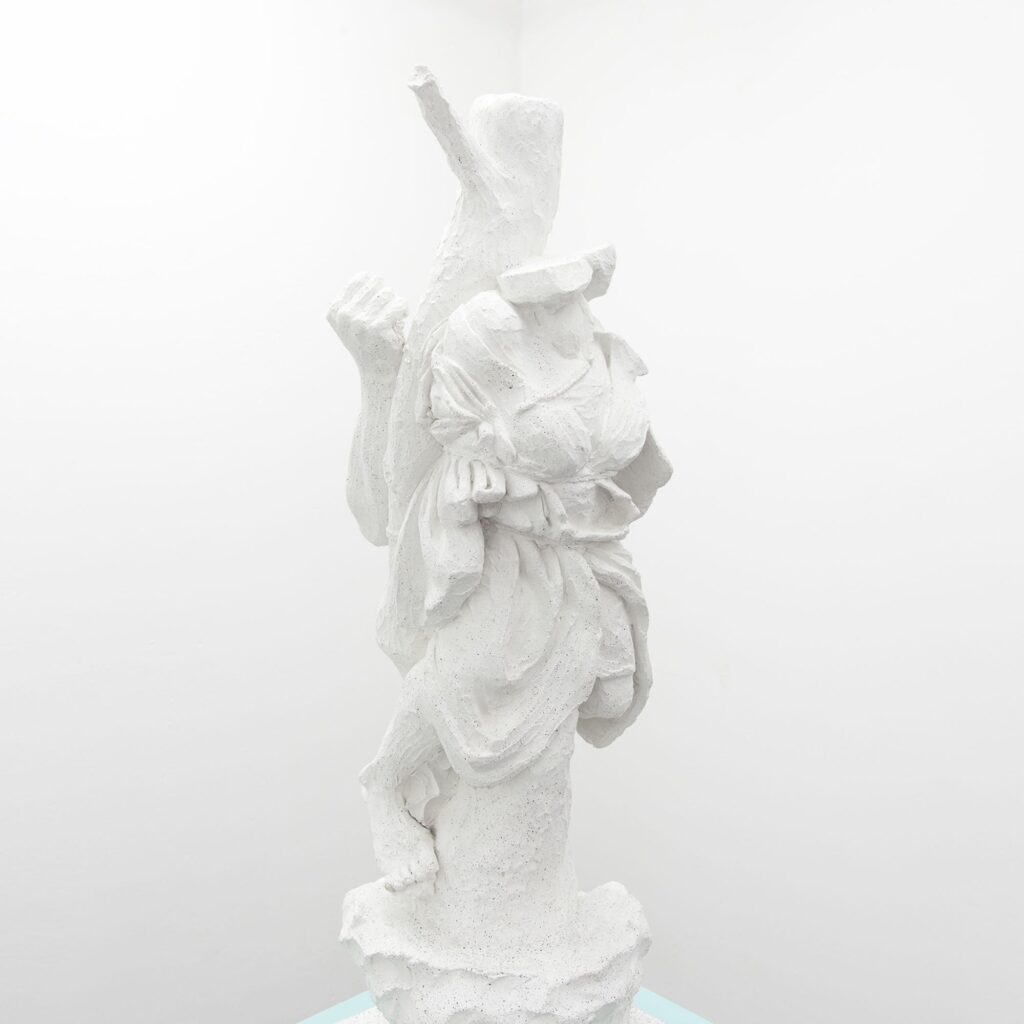

Tramaine de Senna’s sculpture derives from this background of the passiveness and ambiguosity of the tree. Her faceless figure is strapped to a tree, with a lurking, detached arm pulling the rope. Strangely enough, the female figure pushes forward, trying to free herself from the tree. Violence and trauma are written into this scenery while everything is transforming, morphing back and forth between branches and limbs.

Personal history is always interwoven with de Senna’s work. As a descendant of enslaved people in the U.S. she reflects on the question of violence and exploitation. The deformed body is a deformed soul and raises the question of what the difference between living and surviving might be. An image or sculpture can therefore become internalized violence in the form of a material fetishizable object. The disharmony of encapsulating these parallel worlds, to engage in observation and dialogue, are of major significance in de Senna’s pieces.

As the sculpture “Snakes in Paradise” is loosely lifted from a still of Kan Mukai’s movie “Hakkin shibari fujin” (Forbidden Technique to tie a Lady, 1978) the sexual connotations are slightly alleviated, emphasising the tension between incapacitation and violence. The piece transcends the agony and pain you might see and merges into beauty and exuberant defiance. She rides the tree and ultimately leaving it to the observer if it is play or serious. Her disembodiment, the lonely arm is in the end like a line from the Pixies: Where is my mind? Dissolved.